This paper is a final project from the course I teach at the NIH Foundation for Advanced Education in the Sciences — TECH 566: Biotechnology Management

Rachel Gill

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) implemented a roadmap titled “Accelerating Work to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases”, spearheaded by Dr. Lorenzo Savioli, Director, WHO Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases; and Dr. Denis Daumerie, Programme Manager, WHO Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases [1]. The WHO first addressed neglected tropical diseases, or NTDs, on a broad scale in 2003 and in a massive global partnership in 2007; this roadmap is the next major step towards combating NTDs. The roadmap is a follow-up to the report filed in 2010 that highlighted the successes and admitted the shortcomings of the current state of WHO-implemented NTD treatment efforts while revealing the potential economic and tactical feasibility of eliminating NTDs with continued support. This roadmap is in alignment with many of the WHO Millennium Development Goals, which are:

- Poverty alleviation

- Universal primary education

- Promote gender equality and empower women

- Reduced child mortality

- Improved maternal health

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

- Ensure environmental sustainability

- Develop a global partnership for development [2]

The roadmap also highlights an emerging trend in the global biotechnology field – a shift in focus to NTDs and emerging markets. The question arises: what is the potential economic incentive for companies to focus on diseases prevalent in the poorest of nations?

Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs)

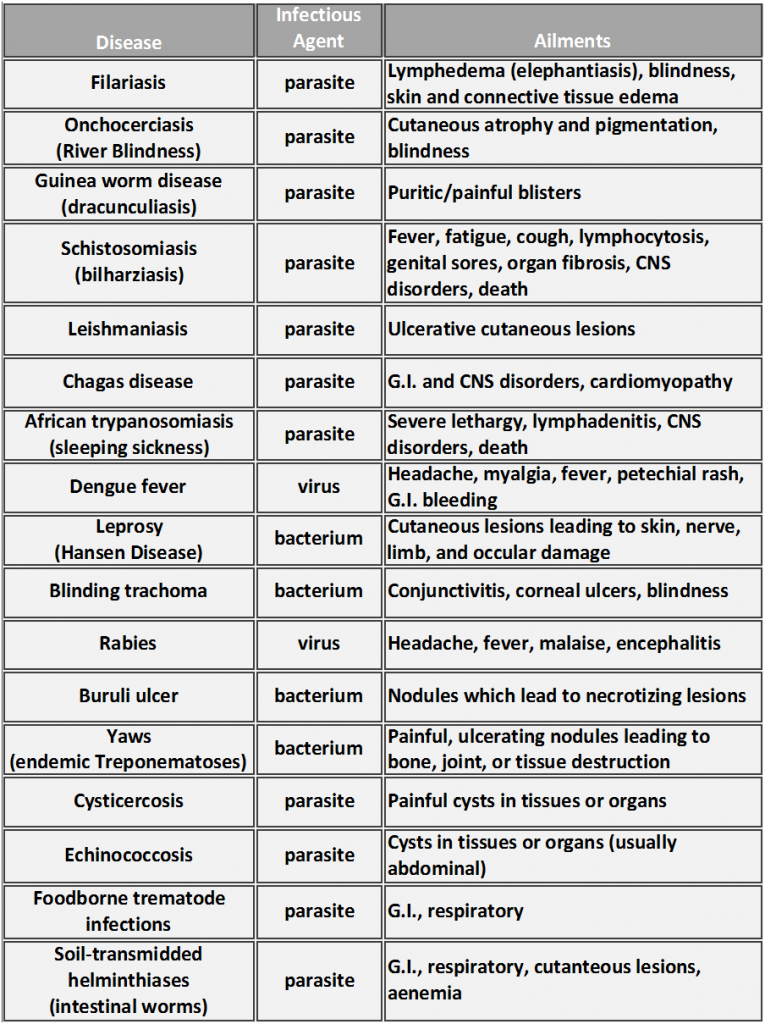

Currently, 17 diseases that affect over 1 billion individuals are recognized by the WHO as NTDs (Table 1)[3]. These diverse ailments have one unifying characteristic– they affect the poorest populations in the world, where the average family lives on less than $2 USD a day [4]. NTDs can be spread through a variety of routes, from contaminated food/water sources to animal vectors. Infections in pregnant women, infants, and young children often result in growth, cognitive, and intellectual deficits that can permanently affect the health and development of the individual. These recurring or chronic infections sustain poverty due to their influence on pregnancy safety, childhood development, and employee output [5].

History of NTDs and WHO Efforts

Initial efforts by the World Health Organization focused on the strategy of yearly or bi-yearly mass drug administration (MDA) in schools; these MDAs mainly utilized mebendazole or albendazole that treat a variety of helminth, or parasitic worm, infections. The initiation of MDA interventions allowed for concise epidemiological delineation of areas affected by certain NTDs, the strengths and limitations of current treatments and diagnostics, as well as how morbidity and mortality rates have decreased since initiation of intervention. For example, in India, lymphatic filariasis was cut in half between 2004 and 2008 [6]. However, Sri Lanka discontinued MDAs, and the South-East Asian countries of Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Timor-Leste still account for the highest burden of filariasis globally. Although there have been successes in treatment of certain infections amongst many populations, intervention is still clearly necessary.

These treatment efforts also highlighted other obstacles for control and eradication of NTDs that included a lack of quick, reliable diagnostics, a small cache of drugs used to treat infections (many with unknown mechanisms of action), parasitic resistance to these drugs, and non-compliance amongst populations. In addition, some approaches are better than others depending on the disease. For instance, vector control would be the best route to curtail Chagas disease, dengue and leishmaniasis, while improved sanitation would aid in controlling Yaws or trematodes.

For NTDs, the primary treatment focus has been on chemotherapeutics, as most of these diseases are parasitic or bacterial, thus warranting vaccine development difficult, if not impossible. Pentamidine and pentamidine analogs were the most heavily investigated compounds for use against parasitic infections. While pentamidine is currently used against African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), it has poor oral bioavailability, does not cross the blood-brain barrier to combat late-stages of the disease, and has nephrotoxic side effects. Analogs are in development, and DB289 developed by Immtech International is in phase III clinical trials [7]. Other target pathways under investigation include enzymes involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis, protease inhibitors, enzymes involved in parasite carbohydrate metabolism, and calcium channel inhibitors [8].

Why are these Diseases Neglected?

Regardless as to any efforts to control and treat NTDs, up until the past decade, researchers, health professionals, and investors have largely ignored these diseases for a number of reasons:

- Failure of first-world relatability. Developed nations with their own wash of problems often find it difficult to relate to the problems of underdeveloped nations. HIV/AIDS, while epidemic in many of these underdeveloped nations, is still a first-world problem, which partially accounts for why so much fundraising, research, and investment occurs to aid both populations. In addition, higher priority is sometimes assessed to mortality over morbidity, as many of these helminthes, viruses, and bacteria classified as NTDs establish life-long infections that sicken or disable, but do not kill, their hosts.

- Nations with NTDs are poor. The countries or areas where NTDs are a problem lack government infrastructure to sufficiently control or eliminate these diseases. Poverty and government instability often lead to civil war, and many of these countries are currently in or have recently witnessed a civil war [9]. As a result, these countries lack government or public institutions like the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that address national health issues. The universities and research institutions that do happen to perform research on NTDs are almost predominantly outside of these regions; war makes it difficult, if not impossible, for outside aid to reach those in need even if treatments are available. Even if outside intervention is able to reach the countries in need, corruption within local governments or organizations can block efficacious drugs from reaching those who desperately need them [10].

- People affected by NTDs are poor. As stated earlier, many of these families live on a few dollars a day and lack proper housing, food, education, and employment. Health care options for these impoverished 1.4 “bottom billion,” as defined by the World Bank, are slim [11]. In these countries, childhood mortality (classified as deaths of children aged 5 or younger) accounts for 94% of all cases of childhood mortality worldwide [12]. These populations do not have access to basic medical care, much less health insurance that could pay for expensive, Big Pharma designer drugs.

- The economy is stagnant. While the global economy has slowly started to recover, the past decade exhibited a contracted economy with fewer investments in research and development and the devaluation of many currencies. While the economy is recovering, worldwide unemployment levels still remain high, as 205 million people are still searching for employment, a number which is up over 30 million since 2007 [13]. Pharmaceutical companies have been especially hard hit, with Big Pharma giants Pfizer, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) announcing major reorganizations and layoffs within their companies [14]. Investment in NTDs was considered by many to be a very high risk venture, and very few biotech companies outside of “Big Pharma” were even willing to take the risk in NTD research [15]. NIH funding has also taken a hit; while adjusting for inflation, the NIH budgets for FY2012 and FY2013 will be $4 billion lower than the peak year of funding (FY 2003) and at the lowest level since FY 2001 [16]. This results in over 3000 fewer grants receiving funding in FY2012-FY2013 than in FY2004.

These are all issues that the roadmap has attempted to address in order to stimulate participation in investment, research, and development of NTD therapeutics. The main purpose of the roadmap is to bring worldwide attention to these diseases, demonstrate that it is feasible to eliminate them, garner more investment towards research and development, and eradicate these ailments to further promote health and economic stability in the affected regions.

Strategies of the WHO NTD Roadmap

The strategies set forth by the roadmap call for elimination or eradication of NTD infections by the year 2020. Many of these NTDs are considered to be “controlled” (“reduction of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity or mortality to a locally acceptable level as a result of deliberate efforts where continued intervention is required”), but the roadmap goals are to eliminate (reduction to or near zero of a disease or infection incidence where intervention is not likely to be required) or eradicate (permanent reduction to zero incidence of a disease where intervention is no longer required) neglected tropical diseases [17]. Total eradication of a disease is not beyond the scope of the WHO; the smallpox global eradication program initiated by the WHO certifiably eradicated smallpox worldwide in the year 1979 [18].

It is the hope that, by outlining specific strategies and milestones while highlighting initial successes, the roadmap will initiate participation from public and private sectors. This premise is based on the investment response that occurred in 2007 after release of the initial report on NTDs by the WHO, which occurred despite being in the midst of a global depression. The generalized strategies to control NTDs by 2020 are:

1. Preventative chemotherapy

2. Intensified disease management

3. Vector and intermediate host control

4. Veterinary public health at the human-animal interface

5. Provision of safe water, sanitation and hygiene

What is the economic incentive for biotech companies to invest in NTD research and development?

Biotechnology can obviously address many, if not all, of the roadmap strategies, and their participation is critical to achieving the goals of the WHO. However, there needs to be an obvious economic incentive for public and private investment in NTD research and development in the current global economy. Initially, drug companies put their focus on diseases with large funding pools (i.e. HIV/AIDS, breast cancer, multiple sclerosis, etc.) or designer drugs that catered to maladies considered to be long-term or lifestyle “first world” problems, such as depression, incontinence, or heart disease. But BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) countries and other emerging markets quickly became the focus of both a manufacturing workforce and a treatment population [19]. With patents expiring on many first-world market drugs and a stagnant worldwide economy, it was inevitable that research and investment strategies would have to refocus [20]. Profits of certain Big Pharmas showed a continual decline over the past decade, with such companies as GSK, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis losing profitability from 2009-2011 [21].

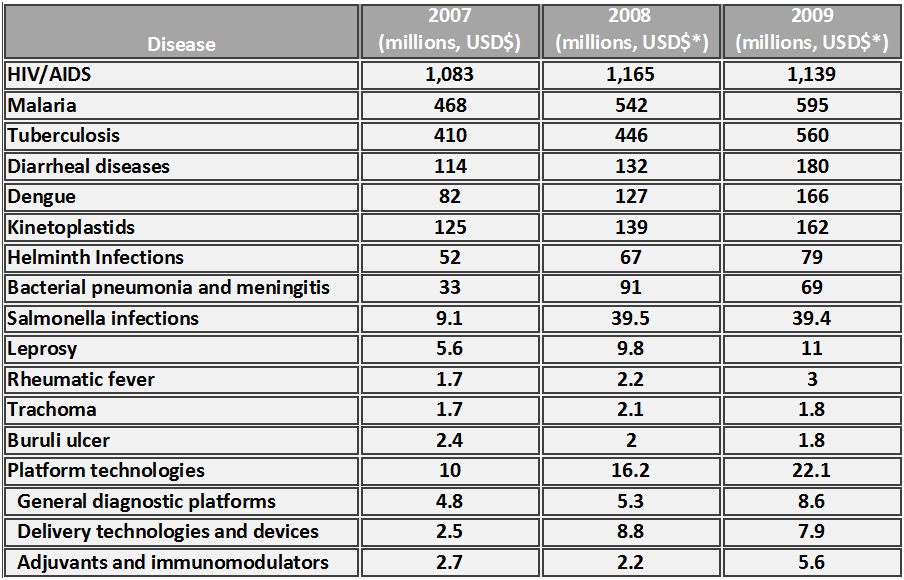

The G-FINDER (Global Funding of Innovation for Neglected Diseases) survey, updated in 2010, set out to compare and contrast research and development funding for NTDs against the “Big Three” (HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria) [20]. This report highlighted the divergence between funding and disease burden, or what is referred to as disability-adjusted life years (DALYs.) While the “Big Three” accounted for 125 million DALYs, NTDs accounted for 165 million DALYs. The funding disparity was enormous, with 80% of available biotech funding dollars going towards the “Big Three” in 2004 and less than 6% towards NTDs. While funding towards NTDs definitely increased from 2004 to the end of the decade- helminth/diarrheal diseases and dengue received approximately $328 million USD in funding- this is merely a drop in the bucket in comparison to the over $2.3 billion in funding received by the “Big Three.” Several NTDs received minimal funding, with leprosy, rheumatic fever, trachoma and Buruli ulcer accounting for a combined total $11 million USD in global infectious disease research and development investment.

For the longest time, the primary funding for NTDs has been more philanthropic, with The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust, and the Sandler Family Supporting Foundation intensifying attention towards this cause with their generous donations and worldwide marketing strategies. However, both public and private research institutions recognized the shift in demand for NTD treatments after the initial reports by the WHO, and increased their internal investments in research and development to account for over 26% of global NTD funding in 2009. Small upward trends in overall research and development investment towards NTDs were apparent from 2007-2009, as the survey performed by the Global Funding of Innovation for Neglected Diseases reported (Table 2.) In 2007 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Amendments Act (HR 3580) initiated the priority review voucher as an incentive for investment in NTDs; this priority review voucher is an award that companies can use on later compounds to accelerate the FDA review of a related or unrelated compound [22].

With the announcement of the WHO roadmap, both public and private organizations pledged large amounts in both research dollars and chemotherapeutic agents. For instance, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation pledged $363 million (USD) towards NTD research over five years. The U.K. Department for International Development also made a five-year pledge in the amount of $315 million (USD). The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) pledged $89 million, while His Highness Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, President of the United Arab Emirates, pledged $10 million (USD). Pharmaceutical companies, in addition to donation of chemotherapeutic agents, also announced product partnerships in the form of licensing and collaboration agreements [23].

What biotechnology companies need to realize is the economic impact is largely in human capital – workers become healthier and smarter, and create more stabilized markets for further investment. Big Pharma can no longer focus solely on designing drugs or vaccines for the developed world, as the economic numbers clearly show that developed economies, while finally expanding again after a massive economic downturn, are only growing at a rate of 2.5% while emerging economies are growing at a rate of 6.5% [13]. Scientific editorials denoted the need for NTDs to be prevented or controlled, as clear associations have been created between economic, political, and environmental destabilization and NTD control [24].

This is not to say that drug companies have completely ignored NTDs. Merck developed ivermectin, a broad-spectrum antiparasitic, which can be taken annually to prevent river blindness (onchocerciasis). Merck announced in 1987 that this drug would be donated for as long as needed to treat river blindness, and over 20 million people have received yearly doses of this drug [25]. Many credit this philanthropic venture by Merck with prompting research into further eradication of not only onchocerciasis, but other NTDs by Big Pharma as donations of anthelmintics were initiated by other pharmaceutical companies (albendazole by GSK, mebendazole by Johnson and Johnson) [26]. Some drugs, such as diethylcarbamazine and praziquantel, are now generic and increasingly affordable for treatment in NTD-affected countries. However, many of these drugs fall short of being extremely efficacious, as most do not kill adult worms, many have deleterious side effects, or the exact treatment dosage has not been optimized [27].

Controlling NTDs Outside Chemotherapeutics

Regardless of these efforts, chemotherapy, while usually the simplest, is not often the best control for NTDs. It tends to be easier to administer a drug once a year to an individual as opposed to creating a sanitation system for an entire village. Vector and intermediate host control, along with improving sanitation infrastructure, are also required to disable the spread of NTDs. Development of mechanisms to aid in these two steps is not entirely outside the realm of biotechnology (i.e. food sanitation, veterinary chemotherapeutics for vector host control, and antibacterial sanitizers or soaps), but the most obvious path of research is in the form of novel chemotherapeutic agents and vaccines.

Development of local infrastructure to implement NTD control and eradication cannot be overlooked, as informed consent and democratic discussions are key in the process of achieving the goals of the WHO. David Canning argues that a “fair and reasonable” decision-making process should address what the local populations feel are the more deleterious problems – while funding and treatment for the “Big Three” remains dominant, communities living with these ailments may weigh the eradication of a specific NTD more heavily than one of the “Big Three” or another NTD [28].

Biotech companies also need to overcome skeptical sentiments amongst certain populations towards outsiders providing treatment, and with good reason. Clinical trials for NTDs is often met with resistance both nationally and internationally, as the human population affected by these diseases are under-educated, impressionable, and impoverished. The predatory nature of certain drug development initiatives has become mainstream in such works as “The Constant Gardener”, which is a film based loosely on Pfizer trovafloxacin (Trovan) trials in Nigeria. In that instance, an estimated 200 children were left permanently disabled and 11 died after treatment within Trovan clinical trials, initiating a lawsuit by the Nigerian government and the refusal by the government to allow its citizens to participate in further clinical trials [29, 30]. In another instance, there was a lack of informed consent with an AZT trial conducted upon HIV-positive women. The purpose of the trial was to determine vertical transmission of HIV in pregnant women; many women in African nations were placed in these trials under duress. In addition, every woman who participated in the United States arms of these trials received some form of antiviral treatment, many of the women in the African arms received placebos [31].

A major setback to overcoming skepticism from these populations is that nations affected by NTDs lack internal research facilities or health organizations to perform research, run clinical trials, or provide treatment. While there are organizations like the Tropical Disease Institute at Ohio University, The Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine at James Cook University, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, or the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium, they are obviously outside the regions affected by NTDs [3]. The WHO has partially addressed this issue by initiating academic or nonprofit drug development centers run by scientists with years of pharmaceutical development experience; these centers were established at University of California, San Francisco; Harvard University, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. However, that is not to insinuate that smaller, local groups were not available to institute measures to control one or more NTD. These groups ranged in focus from control (Onchocerciasis Control Programme in West Africa, the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control, the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, and the Partners for Parasite Control) to eradication (Guinea Worm Eradication Programme, Joint Research Management Committee for Schistosomiasis Elimination in China, the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis, and the Onchocerciasis Elimination Program for the Americas.) Continued success of these organizations and the development of new treatment centers in under-represented areas is dependent upon these research and treatment centers working in conjunction with the WHO and local governments.

Conclusion

In summation, the WHO has initiated a roadmap on elimination and eradication of NTDs, with detailed goals and benchmarks delineated up until the year 2020. While it would be economically beneficial for investors to focus on these emerging markets, it is not enough that companies develop diagnostics or therapeutics for use against NTDs. Biotechnology would be investing in human capital, and the human aspect of this cannot be ignored – aid to stabilize governments, establish local health organizations, and adherence to informed consent are essential to ensure the goals of the WHO are truly realized. DALYs will fall dramatically if biotech increases their research and development towards NTDs, and multiple organizations are providing incentive by increasing the amount of funding support towards research and development of NTD therapeutics. In a somewhat less altruistic note, this will also create a healthier, educated, wealthier market with a demand for currently available therapeutics that are not currently marketed to these populations. Regardless, if biotechnology invests in NTD research, treatment, and philanthropy from the perspective of the populations they are trying to treat, economic gain is inevitable for both the tropical populations and the biotech companies.

References

1. WHO, Accelerating Work to Overcome the Global Impact of Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Roadmap for Implementation. http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2012/WHO_HTM_NTD_2012.1_eng.pdf, 2012, WHO: Geneva.

2. WHO Millenium Development Goals: http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/en/. 2012.

3. Hotez, P.J., Training the next generation of global health scientists: a school of appropriate technology for global health. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2008. 2(8): p. e279.

4. Hotez, P.J., et al., Rescuing the bottom billion through control of neglected tropical diseases. Lancet, 2009. 373(9674): p. 1570-5.

5. Lobo, D.A., et al., The neglected tropical diseases of India and South Asia: review of their prevalence, distribution, and control or elimination. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 2011. 5(10): p. e1222.

6. WHO, Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis progress report 2000-2009 and strategic plan 2010-2020., in WHO2010: Geneva.

7. Immtech Pharmaceuticals Initiates Phase III Pivotal Trial of Pafuramidine Maleate (DB289) to Treat Pneumocystis Pneumonia in HIV/AIDS Patients http://www.immtechpharma.com/documents/news_032706.pdf. 2012.

8. Renslo, A.R. and J.H. McKerrow, Drug discovery and development for neglected parasitic diseases. Nat Chem Biol, 2006. 2(12): p. 701-10.

9. Collier, P., The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it.2007, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

10. Parker, M., T. Allen, and J. Hastings, Resisting control of neglected tropical diseases: dilemmas in the mass treatment of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in north-west Uganda. Journal of biosocial science, 2008. 40(2): p. 161-81.

11. Hotez, P., A handful of ‘antipoverty’ vaccines exist for neglected diseases, but the world’s poorest billion people need more. Health Aff (Millwood), 2011. 30(6): p. 1080-7.

12. Stenberg, K., et al., A financial road map to scaling up essential child health interventions in 75 countries. Bull World Health Organ, 2007. 85(4): p. 305-14.

13. IMF, World Economic Outlook: April 2011. , in Tensions from the Two-Speed Recovery: Unemployment, Commodities, and Capital Flows., I.M. Fund, Editor 2011, World Economic and Financial Surveys: Washington, D.C.

14. Pain, E., The Job Market: A Pharma Industry in Crisis. Science Career Magazine, 2011(Dec. 9, 2011).

15. Trouiller, P., et al., Drugs for neglected diseases: a failure of the market and a public health failure? Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH, 2001. 6(11): p. 945-51.

16. Garrison, H. and K. Ngo NIH Research Funding Trends: FY1995-2012. Policy and Government Affairs: Data Compilations, 2012.

17. Dowdle, W.R. The Principles of Disease Elimination and Eradication. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 1999. 48(SU01), 23-7.

18. WHO Smallpox. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/smallpox/en/. WHO Media centre, 2001.

19. Moran, M., et al., Registering new drugs for low-income countries: the African challenge. PLoS medicine, 2011. 8(2): p. e1000411.

20. Moran, M., et al., Neglected Disease Research and Development: Is the Global Financial Crisis Changing R&D? Global Funding of Innovation for Neglected Diseases http://www.policycures.org/downloads/g-finder_2010.pdf, 2011.

21. CNNMoney/Fortune Fortune 500 Companies: Industries: Pharmaceuticals http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune500/2011/industries/21/index.html. 2011.

22. FDA FDA Approves Coartem Tablets to Treat Malaria http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm149559.htm. 2009.

23. Private and Public Partners Unite to Combat 10 Neglected Tropical Diseases by 2020 http://www.gatesfoundation.org/press-releases/pages/combating-10-neglected-tropical-diseases-120130.aspx. 2012.

24. Hotez, P.J., The neglected tropical diseases and their devastating health and economic impact on the member nations of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2009. 3(10): p. e539.

25. Mackenzie, C.D., et al., Elimination of onchocerciasis from Africa: possible? Trends Parasitol, 2012. 28(1): p. 16-22.

26. JHF, R., B. B, and B. M, Helminth diseases. Onchocerciasis and loiasis. International encyclopedia of public health, ed. H. K and Q. S. Vol. 3. 2008, San Diego: Academic Press.

27. Bockarie, M.J. and R.M. Deb, Elimination of lymphatic filariasis: do we have the drugs to complete the job? Current opinion in infectious diseases, 2010. 23(6): p. 617-20.

28. Canning, D., Priority setting and the ‘neglected’ tropical diseases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2006. 100(6): p. 499-504.

29. Stenver, D.I., J. Ersboll, and J. Renneberg, [Trovan (trovafloxacin/alatrofloxacin) recalled: why? How?]. Ugeskrift for laeger, 1999. 161(30): p. 4311.

30. Court, N.F.H., Federal Republic of Nigeria v. Pfizer, Inc, 2007.

31. Salvi, V. and K. Damania, HIV, research, ethics and women. Journal of postgraduate medicine, 2006. 52(3): p. 161-2.